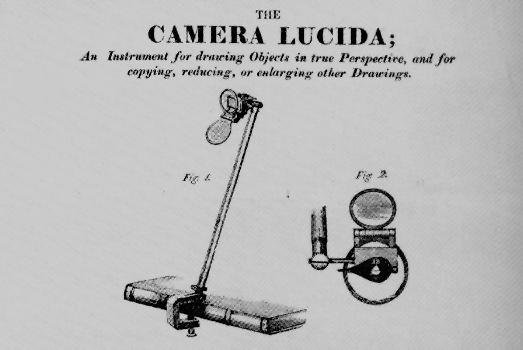

Fig. A - Shows 2 diagrams of the Camera Lucida |

|

The

Making of Audubon's 1st Royal Octavo Edition of Birds of

America using the Camera Lucida. By

Ron Flynn Click here to buy the Audubon Price Guides Even

while working on and finishing the Havell Edition of Birds of America

(1826-1838), John James Audubon was planning his next undertaking; a

smaller more affordable version of Birds of America that would

include omitted and newly discovered species. Referred to as his

“Great Work”, “little edition”, and several other names, it was

to be The 1st Royal Octavo Edition of Birds of America.

The

main reason for producing the octavo edition was to generate income for

the family, and so it became a family project. JJA would be on the road

selling subscriptions and contracting with selling agents. His son

Victor was to run the family’s business affairs from New York.

Finally, son John W. was assigned the job of reducing the double

elephant sized Havell prints to the agreed on octavo size, using the

Camera Lucida.

|

Fig. A - Shows 2 diagrams of the Camera Lucida |

|

THE

CAMERA LUCIDA “The

farther the prism is removed from the paper, that is, the longer the

stem is drawn out, the larger the objects will be represented in the

drawing and accordingly, the less extensive the view.

The nearer the prism is to the paper, the smaller will be the

objects, and the more extensive the view comprised on the same piece of

paper. In

copying drawings, the copy will be larger or smaller than the original,

according as the prism is more or less distant from the paper than it is

from the drawing to be copied. Thus,

if the drawing be two feet from the prism, and the paper only one foot,

the copy will be half the size of the original.

If the drawing be at one foot, and the paper three feet distant,

the copy will be three times as large as the original; and so for all

other distances.” DIRECTIONS

FOR USING THE CAMERA LUCIDA

“The

Instrument being fixed by the screw and clamp to the table and paper on

which the drawing is to be made, its stem should be inclined so as to

bring the prism nearly over the centre of the paper, and the pin, on

which the prism turns, placed truly horizontal. The

Instrument, as represented in the figures, may be used either with the

small round glass, turned up in front, Fig 1, or with the larger glass,

turned up level underneath the Instrument, Figure 2, (seen from above.)

But those who are short-sighted can only use the former, and

persons that are long-sighted must use the latter. The

prism is next to be turned upon its pin, till the transparent

rectangular face be placed opposite to the objects to be delineated,

when the upper black surface of the eye-piece (Figure 2) will be on the

top of the Instrument; and through the aperture in this, the artist is

to look perpendicularly downwards at his paper. The

black eye-piece is moveable, and in ordinary circumstances, is to be in

such a position, that the edge of the small transparent part at the back

of the prism shall intercept about half the eye-hole.

The artist then, looking through the eye-hole directly downwards

at his paper, should see the objects he wishes to draw, apparently

distributed over the paper. For,

since his eye is larger than the eye-hole, he sees through both halves

of the hole at the same time, without moving his head.

He sees the paper through the nearer half, and sees the objects

at the same time through the farther half, apparently in the same

direction, by means of reflection through the prism.” THE

POSITION OF THE EYE-HOLE “The

position of the eye-hole is the circumstance, above all others,

necessary to be attended to in adjusting the Camera Lucida for use; for,

on the due position of this hole depends the possibility of seeing both

the pencil and the objects distinctly at the same time. If

the eye-hole be moved, so that nearly the whole of its aperture be over

the paper, and a pencil and paper will be very faint. But there will always be an intermediate position (varying

according as the objects or the paper happen to be most illuminated) in

which both will be sufficiently visible for the purpose of delineation,

though not quite so clear as to the naked eye.

This intermediate position is easily found, with a little

practice. If

objects can be seen distinctly on the upper part of the paper, but not

upon the lower, the Instrument requires to be turned upon its pin, so

that the transparent face may be inclined rather downwards, and the

contrary for seeing the upper part of the view. Many persons, upon first attempting to use this Instrument, occasionally lose sight of their object or their pencil, merely by means of a little motion of their head, backwards and forwards, of which they are not aware, in breathing; but a very little practice soon obviates this difficulty.” |

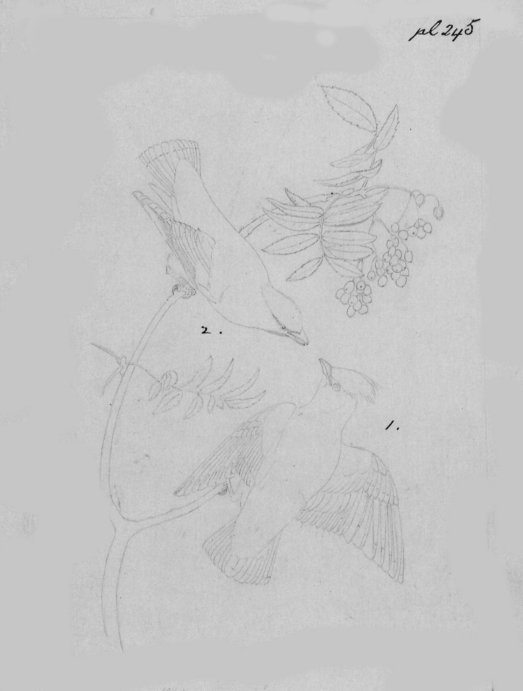

Fig. B - Audubon's Camera Lucida pencil drawing of plate #245, the Black-throated Wax Wing |

|

After

reading

how the Camera Lucida was operated, you can imagine how difficult and

tedious it was to make each drawing. Yet each drawing was only a simple

pencil outline. You will notice the outline of the forked branch, with 3 leaf clusters,

and some flower clusters at the upper right. The 2 birds (1. male and 2.

female) are perched on the forked branch. PRINTING

From

Audubon’s Camera Lucida pencil outline drawing, J.T Bowen’s

lithographic artists would take over.

They would trace over Audubon’s outline drawing with a red or

brown pencil, and then place it face down on the lithographic stone. By

rubbing over the back of the Camera Lucida drawing, they would transfer

the image to the lithographic stone. The lithographic artist would then

fill in and add details on the stone, using special greasy or waxy

crayons, to complete the drawing. Finally, bathing the stone in gum

Arabic and nitric acid to “fix” the drawing finishes the stone. It

is then ready for the pressroom. R. Trembley and W.E. Hitchcock were the

most noted of all of Bowen’s lithographic artists. The

skill of the pressmen is just as important as that of the lithographic

artist in producing a quality print. The stone is wetted and then sticky

greasy black ink is applied with a roller. The ink adheres to the greasy

crayon drawing on the stone, but is repelled by the blank wet areas of

the stone. The pressmen or printer lays a sheet of paper on the stone,

and using the press applies tremendous pressure. He then “pulls” the

print off the lithographic stone. After drying, the prints are ready for

hand coloring.

|

|

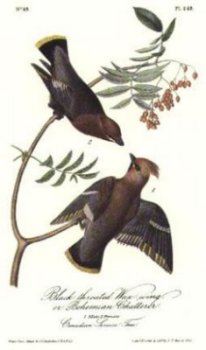

Fig. C an uncolored print of plate #245 the Black-throated Wax Wing |

|

HAND

COLORING J.T.

Bowen employed the best colorists available in Philadelphia. He

patterned his “studio” after the Currier & Ives shop in New

York. Teams of colorists, mostly young women, sat around long tables.

Each table would have a model or colored proof, approved by one of the

Audubons, displayed for all to see. Each colorist would be assigned a

specific section of the print, and only one color to apply. The print

would be passed around the table until it was fully colored. It would

then pass to a “finisher”, at the head of the table, who would check

and complete the print with touchups and highlighting. After

drying, the finished colored prints were undoubtedly stored in a series

of individual bins, where they could be easily pulled to fill

subscription orders as they arrived.

|

|

Fig. D a finished hand colored print of plate #245 the Black-throated Wax Wing

|

|

|

BIBLIOGRAPHY Durant,

Mary and Harwood, Michael, On The Road With John James Audubon,

1980 Flynn

Family Trust, Permanent Art Collection Hill Memorial Library, Louisiana State UniversityTyler,

Ron, Audubon’s Great National Work, 1993 Click here to buy the Audubon Price Guides Copyright © 2008 by, Ron Flynn, ALL RIGHTS RESERVED Ron Flynn, 796 Holly Creek Dr., Holland, MI 49423 |